“You scholars are inconsistent!”

“You reject evolutionary science, dismiss calculation based Islamic calendars, but suddenly champion science when using astronomical calculations to negate witness testimony.”

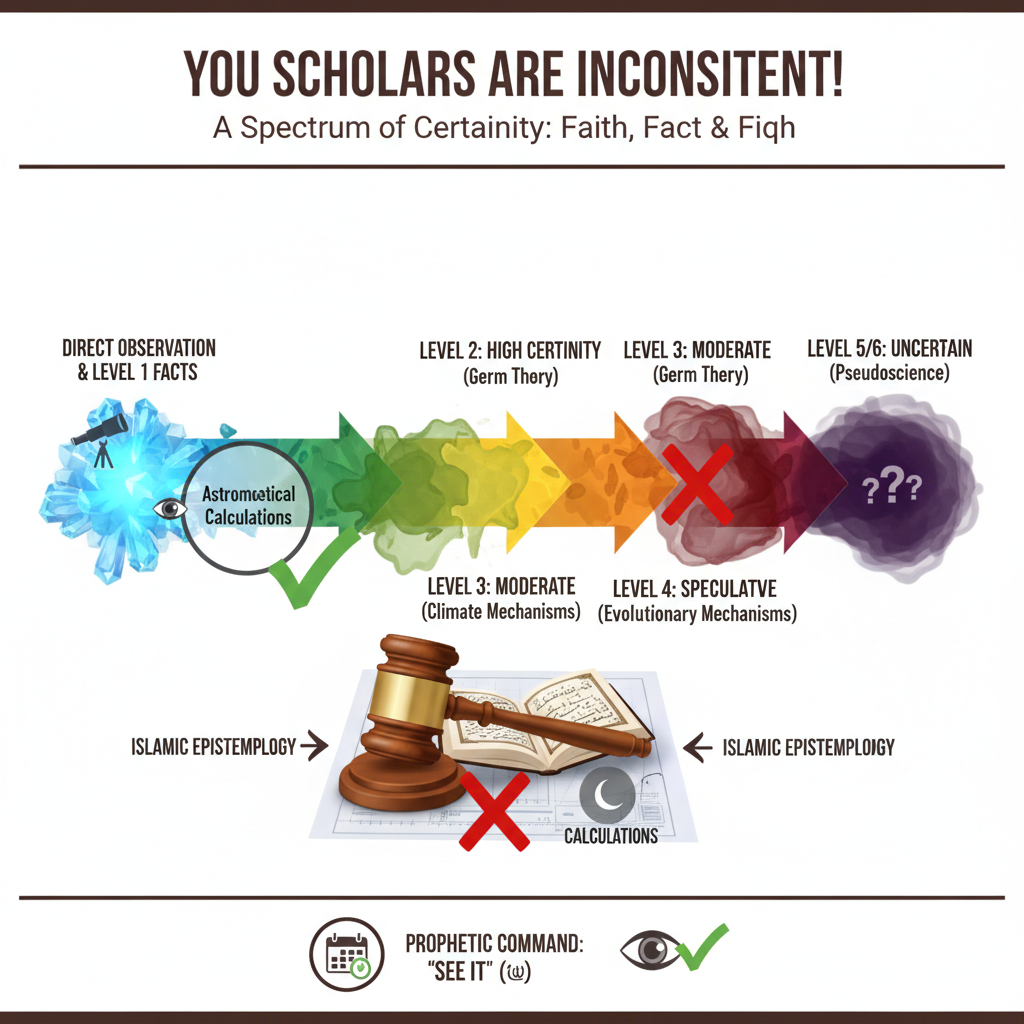

The Real Issue: Understanding the Spectrum of Scientific Knowledge

This isn’t about cherry-picking science. This is about understanding the fundamental differences in scientific claims – a nuanced approach that demands intellectual rigor.

Scientific Knowledge: A Spectrum of Certainty

Imagine scientific knowledge as a river flowing from crystal-clear certainty to murky speculation:

| Level | Characteristics | Reliability | Changeable | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | Directly Observable Scientific Facts | Absolute Certainty | No | Astronomical Calculations |

| Level 2 | Extensively Verified | Very High Certainty | Rarely | Germ Theory |

| Level 3 | Robust Evidence | High Certainty | Sometimes | Climate Mechanisms |

| Level 4 | Significant Evidence | Moderate Certainty | Often | Evolutionary Mechanisms |

| Level 5 | Limited Evidence | Low Certainty | Frequently | Consciousness Theories |

| Level 6 | Minimal Evidence | No Certainty | Yes | Pseudoscience |

For Level 1 scientific facts, the only thing that could overturn them would be a miracle—something that breaks the established order of the universe itself. For levels 2-6, they can change with new data revealed or different interpretations of the data.

Direct Sensory Experience: The Foundation of Knowledge

Before discussing scientific knowledge, we must understand direct sensory experience:

- Seeing something with your eyes

- Touching an object

- Hearing a sound

- Smelling a fragrance

- Tasting food

These are NOT science. They are raw observations – the fundamental building blocks from which scientific investigation begins. Direct sensory experience provides immediate, personal information about the world.

Islamic Epistemological Sources: What Counts as Knowledge?

In Islamic scholarship, epistemology refers to how we know what we know. It asks: What are the valid sources of knowledge? Which of them provide certainty? Which of them are speculative?

Islamic scholars recognize four primary sources of knowledge:

- Sensation (Hiss – الحس): This includes what we know through our five senses. Within this source:

- Direct Sensory Experience provides absolute certainty.

- Level 1 Scientific Facts—those that are directly observable and consistently repeatable—also provide absolute certainty.

- Anything below Level 1 in science, such as theories based on interpretation or incomplete data, may change with new discoveries or alternative explanations.

- Reason (Aql – العقل): Clear, logical reasoning that is free from contradiction.

Revelation (Wahy – الوحي): Divine guidance from the Qur’an and authentic Sunnah.

Truthful Testimony (Khabar Saadiq – خبر صادق): Verified reports from trustworthy sources.

Islamic Epistemological Sources of Certain Knowledge

In Islamic scholarship, knowledge is categorized based on its level of certainty. Not all sources of knowledge are equal. Some provide absolute certainty (yaqin), while others offer probable knowledge (zann).

Sources of Certain Knowledge in Islamic Epistemology

| Source | Arabic Term | Certainty Level | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Sensory Experience | Hiss (حس) | Certain Knowledge | Immediate, personal observations through the five senses |

| Level 1 Scientific Facts | Part of Hiss | Certain Knowledge | Directly observable, universally consistent scientific facts |

| Decisive Revelation | Wahy Qat’i (وحي قطعي) | Absolute Certainty | Clear, unambiguous divine revelation |

| Definitively Established Reason | Aql Qat’i (عقل قطعي) | Certain Knowledge | Logically irrefutable reasoning |

| Truthful Testimony | Khabar Saadiq (خبر صادق) | Conditionally Certain | Reliable testimony from trustworthy sources |

Key Distinctions

- Direct sensory experience provides immediate, personal certainty

- Level 1 scientific facts are a subset of direct sensory experience

- Not all scientific claims provide certain knowledge

- The highest form of certainty comes from decisive revelation combined with clear observation

We Are Not Telling You to Trust Any And All Science

The point here is not to accept every scientific claim blindly. A principled approach to science involves discerning the level of certainty a claim offers and weighing it against established sources of knowledge.

Take the example of evolution. A Muslim can, on solid epistemological grounds, reject macroevolution—the idea that all life descended from a common ancestor through gradual, unguided change over millions of years. This is not a directly observable fact. It falls under Level 4 scientific knowledge, involving significant interpretation, assumptions, and extrapolation over unseen timescales.

In contrast, astronomical calculations related to the sun and moon fall under Level 1. They are grounded in repeated observation, measurable phenomena, and direct calculation. They are consistent, testable, and confirmed by things like eclipse predictions. Accepting one and rejecting the other is not inconsistency—it’s discernment based on the strength of evidence.

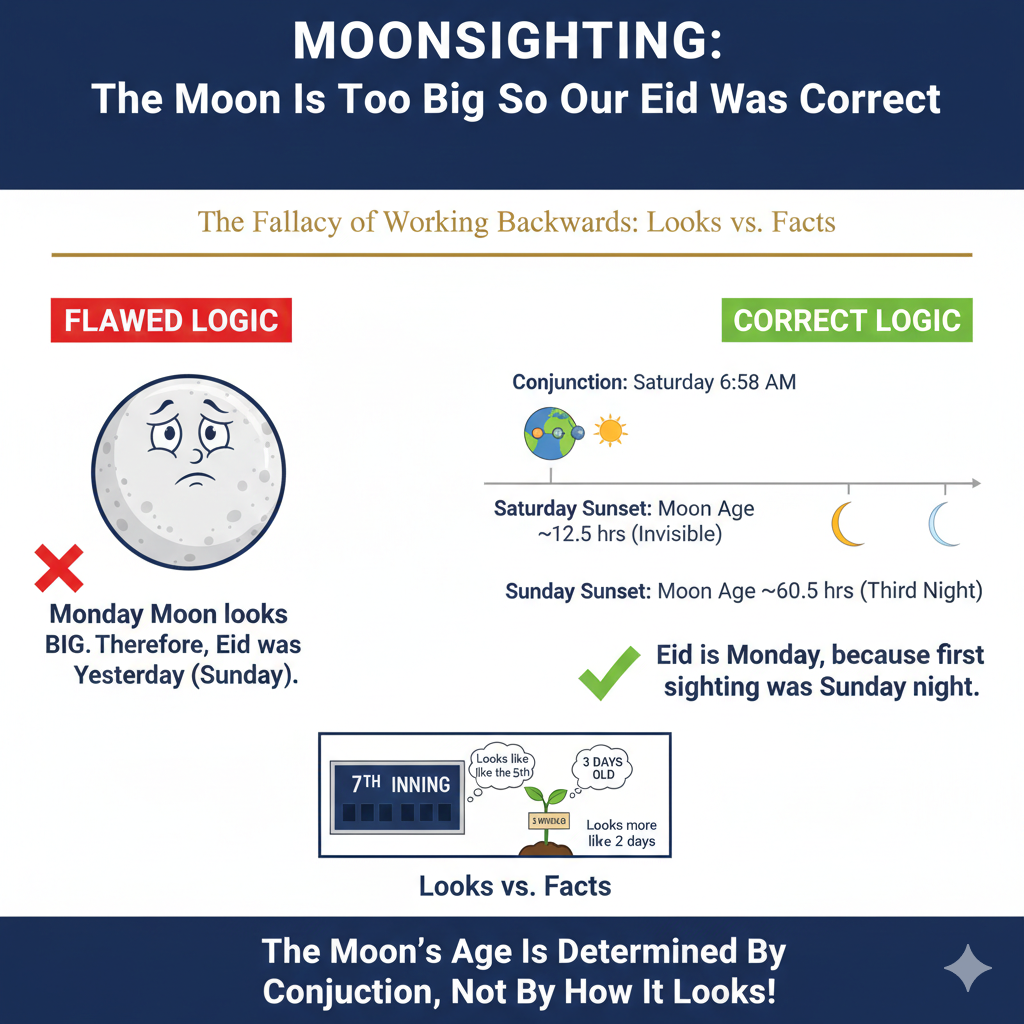

Certainty in Astronomical Calculations

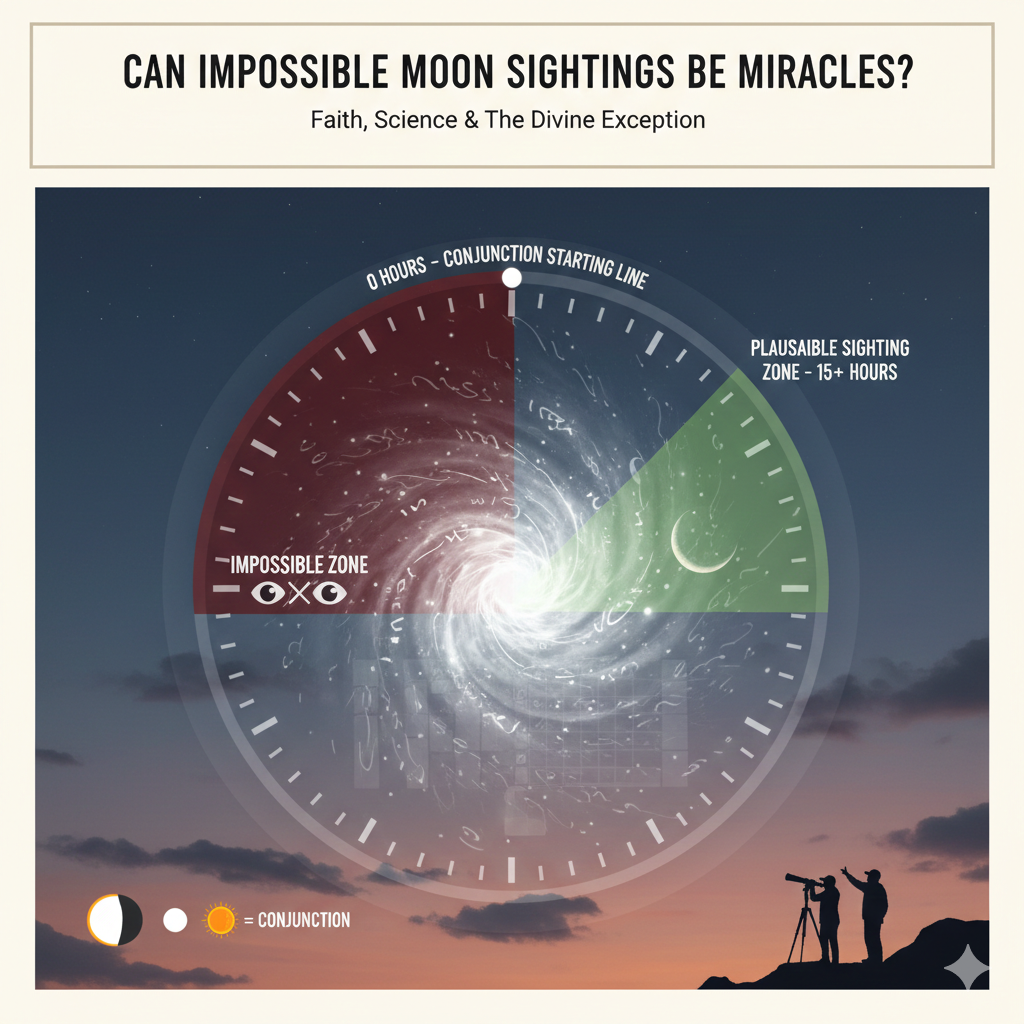

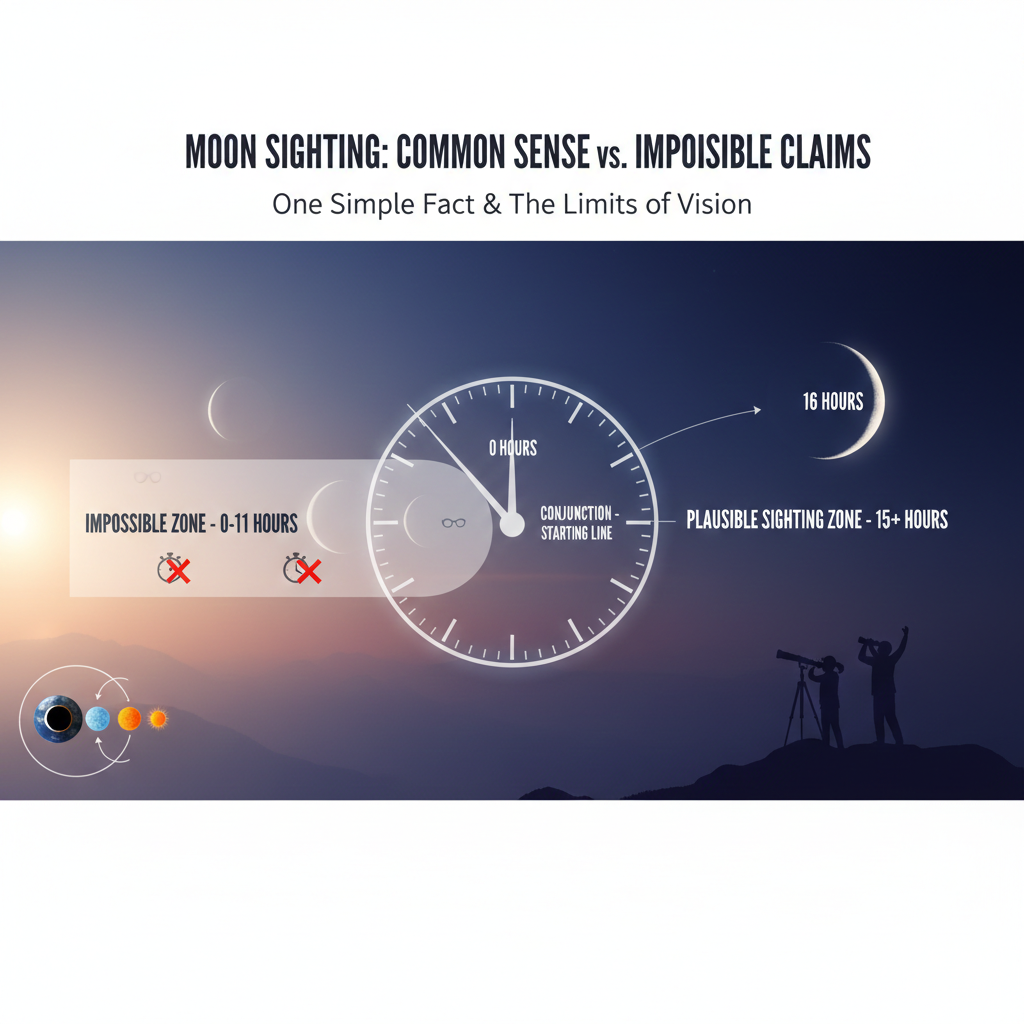

Astronomical calculations used to determine moon visibility—such as whether the moon can be seen four hours after conjunction—fall under Level 1 Scientific Facts. These are not speculative models. They are based on direct measurement, observation, and consistent physical laws.

The certainty of such calculations is equivalent to other physical facts: water boiling at 100°C at sea level, or the earth’s orbit around the sun. These are directly measurable and universally consistent. As such, they provide absolute certainty.

One powerful confirmation of this certainty is the precise prediction of solar and lunar eclipses. These events are forecasted years—even decades—in advance and occur exactly as calculated, down to the second. This level of accuracy is only possible because the underlying astronomical data is fully within the realm of Level 1 science.

Rejecting these calculations would not be a matter of differing scholarly interpretations; it would imply a break from empirical certainty, requiring the extraordinary—such as a miracle or a suspension of natural laws—for them to be wrong.

If So Accurate, Why Not Use Calculations To Start The Islamic Lunar Month?

Grounding in Islamic Legal Methodology

The reason is that the basis of this has nothing to do with its accuracy or lack thereof. This approach is grounded in fundamental principles of Islamic legal interpretation:

A Direct Prophetic Command

The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ instructed: “Fast when you see it (the crescent) and break your fast when you see it…” (Bukhari and Muslim). The word “see” (ru’yah) clearly refers to visual observation with the human eye.

Why Literal Meanings Matter

Taking words at their apparent meaning (dhaahir) is essential in Islamic textual understanding. If we decide “seeing the moon” actually can mean “calculating the moon’s position,” we open a dangerous door that undermines not only the entire foundation of Islamic practice but also the basic function of human language itself.

Scholars who insist on the literal meaning of “seeing” in this context aren’t merely being rigid about one particular issue – they are defending a fundamental interpretive principle that protects the entire religion. This principle of adhering to the apparent meaning of texts (haqiqah) unless compelling evidence indicates otherwise is what preserves the integrity of Islamic law and practice across all domains.

Everyday Examples that Clarify the Point

Consider how arbitrary reinterpretation undermines clear communication:

- If a legal document says “sign on the dotted line,” would you consider typing your name elsewhere or drawing a star symbol to fulfill this requirement? Of course not! The word “sign” clearly means writing your signature in the specific indicated location.

- When a warranty states “proof of purchase must be presented for all returns,” would any store accept that you simply described your purchase experience verbally without showing a receipt? The meaning of “presented” obviously requires physically showing the document.

- If a medical consent form states “patient must initial each page,” would any doctor accept mathematical calculations about your name instead of your actual handwritten initials? This would completely change what’s being requested.

- When a tax form instructs you to “attach W-2 form here,” would the IRS consider it compliance if you merely calculated your income without including the actual document? The instruction clearly calls for the physical document.

These examples show how replacing the apparent meaning with an alternative interpretation fundamentally changes the nature of what’s being asked. Similarly, when the Prophet ﷺ said to “see the crescent,” reinterpreting this to mean “calculate its position” changes a direct sensory instruction into a completely different mental activity.

How Subtle Changes Distort Practice

Consider these examples that show how changing the meaning of a single word transforms religious practice:

- When Allah commands us to “obey the Messenger,” all Muslims understand the word “obey” to mean actually following his instructions as given. If we allowed “obey” to also be interpreted as “consider his advice while making your own judgment,” the entire concept of religious authority would be undermined.

- When the Quran instructs Muslims to “lower their gaze,” the word “lower” is understood as physically directing one’s eyes downward away from inappropriate sights. If we reinterpreted “lower” to mean “mentally ignore while still looking,” the physical action explicitly commanded would be replaced with a mere internal attitude.

In the same way, when the Prophet ﷺ explicitly instructed Muslims in the hadith: “Fast when you see it (the crescent) and break your fast when you see it” (صوموا لرؤيته وأفطروا لرؤيته) as reported in Bukhari and Muslim, the word “see” (رؤية/ru’yah) unambiguously refers to visual observation with the human eye. If we allowed “see” in this hadith to also be interpreted as “determine through calculation,” we would be changing the fundamental nature of the command from a physical action (looking with the eyes) to a mental exercise (calculating positions). This would not only contradict the Prophet’s ﷺ clear intent but would open the door to reinterpreting other explicit commands throughout Islamic texts.

Each of these examples shows how changing just one key word’s meaning can fundamentally alter religious practice while seeming to maintain some connection to the original command.

Guarding the Integrity of Revelation

When scholars stand firm on this point, they’re not just defending moon sighting – they’re guarding the methodological foundation upon which our understanding of all Islamic texts is built. If this principle is compromised for convenience in one area, the same logic can be applied elsewhere, gradually eroding the entire framework of textual interpretation.

This isn’t about being rigid – it’s about being principled and consistent. When we accept arbitrary departures from apparent meaning in one area, we undermine the entire textual foundation of the religion and the very possibility of clear communication.

So the reason for not using astronomical calculations to start the month has nothing to do with their accuracy or lack thereof. It is connected to when the Prophet ﷺ explicitly told us to start it.

The Depth Behind the Tradition

It may be surprising that such nuance, classification, and careful reasoning comes from the very Islamic scholars who are often dismissed as simplistic or out of touch. But this depth of thought should serve as a quiet reminder: Islamic scholarship is built on centuries of rigorous engagement with revelation, reason, and reality.

Rather than being unaware of scientific progress, these scholars understand it—and more importantly, they understand where and how it fits within a broader framework of knowledge. That framework is not improvised. It is inherited, disciplined, and principled.

Placing things in their rightful categories—what is certain, what is speculative, what is divine, and what is empirical—is not rigidity. It is intellectual clarity. It is this clarity that preserves the distinctiveness of Islamic law, the authority of revelation, and the value of science—without collapsing one into the other.

The thoughtful reader may come to see that what once appeared as stubbornness may actually be a principled and precise defense of coherence and consistency across all domains of human understanding.

Conclusion

Not Anti-Science, but Epistemologically Grounded

This discussion is not about being anti-science, nor is it about selective skepticism. It is about understanding knowledge through a principled lens rooted in Islamic epistemology. Islam teaches us to differentiate between what is directly observable, what is logically certain, what is divinely revealed, and what is merely probable.

The Spectrum of Scientific Knowledge

Scientific knowledge exists on a spectrum—from absolute, repeatable facts to speculative and interpretive theories. As Muslims, we are not only permitted but expected to critically evaluate where on this spectrum a scientific claim lies before integrating it into religious judgment.

Rejecting Speculation, Accepting Certainty

This is why a Muslim may firmly reject macroevolution on solid epistemological grounds—because it falls into the category of interpretive and speculative science, built on assumptions and unobserved processes. At the same time, the same Muslim may affirm the certainty of astronomical calculations, because they belong to a domain of science that is repeatable, observable, and universally confirmed.

The Case of the Moon and Prophetic Instruction

We accept astronomical calculations as Level 1 scientific facts because they meet the criteria of certainty and observability. But we do not use them to start the lunar month—not because we doubt the science, but because we honor a specific command from the Prophet ﷺ that is clear, deliberate, and rooted in divine instruction.

Coherence, Not Contradiction

This is not a contradiction. It is a coherent, disciplined approach to knowledge that preserves both intellectual integrity and religious fidelity. It is about understanding knowledge through a principled lens rooted in Islamic epistemology. Islam teaches us to differentiate between what is directly observable, what is logically certain, what is divinely revealed, and what is merely probable.